It could be a tale told by Scheherazade from the 1001 nights and set in the times of the Great Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid. A tale of the Banu Sasan. A tale of poets and rogues, of vagabonds and bandits and of charlatans and disinherited second sons.

Fraternities of criminals and outlaws have probably existed from the earliest time when “laws” were first invented and “outlaws” were banished. Of course “laws” were established by whoever was strong enough to enforce them and the label of “criminality” applied to a group only as long as the group was not dominant. (Once a gang was strong enough it became legitimate and would now be called a “political party”). Organised crime and criminal fraternities that we might recognise as “gangs” therefore date back at least to the initial formation of cities and the exclusion of people outside those early city walls. The origin of gangs probably lies in the loose cooperation between such “outsiders” and “outlaws” and probably goes back some 5,000 years. In Ancient Greece, in the 7th and 8th centuries BCE, “criminal gangs” – for want of a better term – had to be put down when the city states were established. There are suggestions of “criminal fraternities” / rebels in the Roman Empire, in Byzantium and even among the Aztecs.

The romanticism of Robin Hood and his ilk comes later but is still alive today. The success of The Godfather would suggest that even the Mafia can be seen through romanticised eyes. Certainly modern day gangs – whether in the Balkans or in Los Angeles or in Afghanistan or in the jungles of Chattisgarh – still succeed in recruiting young members who see themselves as “freedom fighters” or rebels against an unjust society. As Kings and Vagabonds.

The Smithsonian’s Past Imperfect Blog carries the story of the Banu-Sasan.

Abbasid Caliphate at its greatest extent, c. 850: Wikipedia

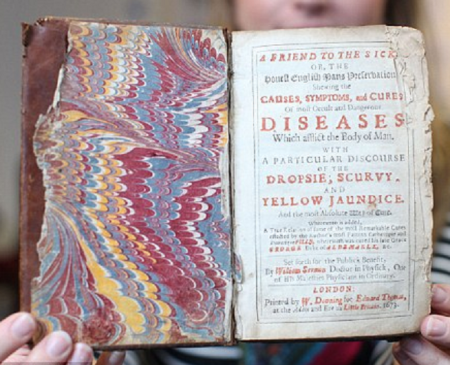

The year is—let us say—1170, and you are the leader of a city watch in medieval Persia. Patrolling the dangerous alleyways in the small hours of the morning, you and your men chance upon two or three shady-looking characters loitering outside the home of a wealthy merchant. Suspecting that you have stumbled across a gang of housebreakers, you order them searched. From various hidden pockets in the suspects’ robes, your men produce a candle, a crowbar, stale bread, an iron spike, a drill, a bag of sand—and a live tortoise.

The reptile is, of course, the clincher. There are a hundred and one reasons why an honest man might be carrying a crowbar and a drill at three in the morning, but only a gang of experienced burglars would be abroad at such an hour equipped with a tortoise. It was a vital tool in the Persian criminals’ armory, used—after the iron spike had made a breach in a victim’s dried-mud wall—to explore the property’s interior.

We know this improbable bit of information because burglars were members of a loose fraternity of rogues, vagabonds, wandering poets and outright criminals who made up Islam’s medieval underworld. This broad group was known collectively as the Banu Sasan, and for half a dozen centuries its members might be encountered anywhere from Umayyad Spain to the Chinese border. Possessing their own tactics, tricks and slang, the Banu Sasan comprised a hidden counterpoint to the surface glories of Islam’s golden age. They were also celebrated as the subjects of a scattering of little-known but fascinating manuscripts that chronicled their lives, morals and methods..

According to Clifford Bosworth, a British historian who has made a special study of the Banu Sasan, this motley collection of burglars’ tools had some very precise uses:

The thieves who work by tunneling into houses and by murderous assaults are much tougher eggs, quite ready to kill or be killed in the course of their criminal activities. They necessarily use quite complex equipment… [The iron spike and an iron hand with claws] are used for the work of breaking through walls, and the crowbar for forcing open doors; then, once a breach is made, the burglar pokes a stick with a cloth on the end into the hole, because if he pokes his own head through the gap, [it] might well be the target for the staff, club or sword of the houseowner lurking on the other side.

The tortoise is employed thus. The burglar has with him a flint-stone and a candle about as big as a little finger. He lights the candle and sticks it on the tortoise’s back. The tortoise is then introduced through the breach into the house, and it crawls slowly around, thereby illuminating the house and its contents. The bag of sand is used by the burglar when he has made his breach in the wall. From this bag, he throws out handfuls of sand at intervals, and if no-one stirs within the house, he then enters it and steals from it; apparently the object of the sand is either to waken anyone within the house when it is thrown down, or else to make a tell-tale crushing noise should any of the occupants stir within it.

Also, the burglar may have with him some crusts of dry bread and beans. If he wishes to conceal his presence, or hide any noise he is making, he gnaws and munches at these crusts and beans, so that the occupants of the house think that it is merely the cat devouring a rat or mouse.

The Iranica informs us:

“BANŪ SĀSĀN, a name frequently applied in medieval Islam to beggars, rogues, charlatans, and tricksters of all kinds, allegedly so called because they stemmed from a legendary Shaikh Sāsān. A story frequently found in the sources, from Ebn al-Moqaffaʿ onward, states that Sāsān was the son of the ancient Persian ruler Bahman b. Esfandīār, but, being displaced from the succession, took to a wandering life and gathered round him other vagabonds, thus forming the “sons of Sāsān.”

The Smithsonian continues:

Who were they, then, these criminals of Islam’s golden age? The majority, Bosworth says, seem to have been tricksters of one sort or another,

who used the Islamic religion as a cloak for their predatory ways, well aware that the purse-strings of the faithful could easily be loosed by the eloquence of the man who claims to be an ascetic or or mystic, or a worker of miracles and wonders, to be selling relics of the Muslim martyrs and holy men, or to have undergone a spectacular conversion from the purblindness of Christianity or Judaism to the clear light of the faith of Muhammad.

Amira Bennison identifies several adaptable rogues of this type, who could “tell Christian, Jewish or Muslim tales depending on their audience, often aided by an assistant in the audience who would ‘oh’ and ‘ah’ at the right moments and collect contributions in return for a share of the profits,” and who thought nothing of singing the praises of both Ali and Abu Bakr—men whose memories were sacred to the Shia and the Sunni sects, respectively. Some members of this group would eventually adopt more legitimate professions—representatives of the Banu Sasan were among the first and greatest promoters of printing in the Islamic world—but for most, their way of life was something they took pride in. One of the best-known examples of the maqamat (popular) literature that flourished from around 900 tells the tale of Abu Dulaf al-Khazraji, the self-proclaimed king of vagabonds, …

“I am of the company of beggar lords,” Abu Dulaf boasts in one account,

the cofraternity of the outstanding ones,

One of the Banu Sasan…

And the sweetest way of life we have experienced is one spent in sexual indulgence and wine drinking.

For we are the lads, the only lads who really matter, on land and sea.

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BCE according to the Kurgan hypothesis. Wikipedia

The ethnic composition of the Banu Sasan is the subject of much speculation. The nomadic Banu Sasan are said by some to have been one of the drivers of the spread of “indo-European”peoples and languages. Perhaps the Banu Sasan may have had links with the ancient Tocharians. But it is more likely that the Banu Sasan was more a fraternity of occupation(s) and not of ethnicity. There are suggestions that there may be genetic connections between those of the Banu Sasan to present-day Roma (the Boyash or the Rudari) and to Parsis and even some Jews. That of course is quite possible for no doubt these vagabond poets and beggar-lords had their share of girl-friends at every caravanserai to be found.